It’s probably a sign of getting older, but I find the obituaries in the Times of London the most interesting part of the paper these days (standing that they never publish what they’d probably categorise as my left-wing republican indy-leaning rants in the letters page). It almost goes without saying that to get an obit in the Times you generally have to have lived an interesting life: and, even now, in 2024, centenarians who lived through the Holocaust, or saw action in the skies over Europe during the Second World War, are having their remarkable histories memorialised.

It’s probably a sign of getting older, but I find the obituaries in the Times of London the most interesting part of the paper these days (standing that they never publish what they’d probably categorise as my left-wing republican indy-leaning rants in the letters page). It almost goes without saying that to get an obit in the Times you generally have to have lived an interesting life: and, even now, in 2024, centenarians who lived through the Holocaust, or saw action in the skies over Europe during the Second World War, are having their remarkable histories memorialised.

Others have found different ways to be remarkable. A recent example was Malachy McCourt, variously described as professional Irishman, raconteur, writer, pub owner, actor and gadabout, who died at 92 after a life rambunctiously lived.

Things did not begin well for Malachy and his elder brother, Frank. Born in Brooklyn, where his alcoholic father had temporarily relocated under suspicion of being an IRA terrorist, he moved back with his family to the slums of Limerick 3 years later into a life of almost unbelievable poverty, one which Frank was to convert into literary gold in the Pulitzer-prize winning Angela’s Ashes (Malachy’s own memoir, A Monk Swimming, is apparently much funnier).

Funded by Frank, who had found work as a teacher, he managed to return to New York aged twenty one with no qualifications and fewer prospects. Starting on the bottom rung as a dishwasher, within a few years his magnetic charm had led famous friends to bankroll him into opening what became New York’s first singles bar.

However, a restless spirit and the vagaries of drinking led him into various scrapes and  high jinks, including smuggling gold from Switzerland to India; hosting a talk show that was cancelled after ten days but still managed to feature Richard Harris, Sean Connery and Muhammad Ali; appearing as an actor in the Molly Maguires, The Brink’s Job and three different soap operas; and joshing with Prince Philip about George III’s loss of his American colonies. He also appeared, drunk, on many talk shows (McCourt, that is: the Duke of Edinburgh wasn’t allowed on talk shows).

high jinks, including smuggling gold from Switzerland to India; hosting a talk show that was cancelled after ten days but still managed to feature Richard Harris, Sean Connery and Muhammad Ali; appearing as an actor in the Molly Maguires, The Brink’s Job and three different soap operas; and joshing with Prince Philip about George III’s loss of his American colonies. He also appeared, drunk, on many talk shows (McCourt, that is: the Duke of Edinburgh wasn’t allowed on talk shows).

A ready wit and an Irishman’s gift with words supersized such exploits into mythic proportions. A brief job selling Bibles ended when he realised ‘you can’t sell a product you don’t believe in.’ Giving up drinking after his father’s death in 1985, even the prospect of his own demise didn’t faze him, humans, he explained, having ‘a 100% mortality rate.’

Speaking in 2019, he said, ‘I hear people talking about going to Heaven. Why would you want to go there? To sit at the right hand of God, looking into his earlobe for eternity? I wouldn’t want to be with him. I’m with Dorothy Parker: “Heaven for the comfort, Hell for the company.”‘ Personally, I rather hope the Big Man makes an exception, and gives him freedom of movement between the two places.

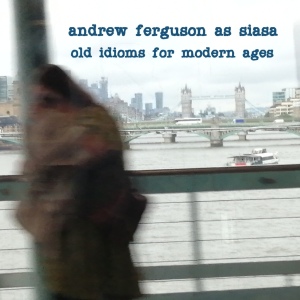

Reflecting on Malachy McCourt brings me to a song on my next album, ‘The Last Time I Saw Gabriel.’ It wasn’t inspired by McCourt’s story – I knew nothing about him until his obit ran the other day – but by a passing reference made by a friend, himself a larger than life character, to someone he knew. ‘He’s still out there for all of us,’ my friend said, relating a story of the guy, now in his late fifties, getting locked out of his fancy hotel room on a work trip. There were fire extinguishers and police involved, apparently.

There’s something compelling about characters like that, isn’t there, for the rest of us ordinary civilians? It’s easy to forget, in the case of Malachy McCourt, for example, the years of grinding poverty and the after effects of alcoholism that led him into such extreme, risk-taking behaviour. It’s all fun and games until you wake up in a jail cell with gaps in your memory the breadth of the Hudson.

On the other hand, there’s also a risk in ending up like the narrator in ‘Gabriel’: becoming an observer of life instead of living it yourself, keeping a notebook close.

So let’s raise a glass to a great Irishman, professional or otherwise, and next time the Malachy McCourt in your life leads you off into deeper waters, don your scuba gear and get involved. The worst thing that can happen is you have a tale to tell with yourself a lead participant.

Most times, at least.

I’m pretty sure I haven’t read anything by either of the McCourt brothers, which, if correct, is a very big oversight on my part. And I automatically give them a thumbs-up, because they were born in Brooklyn, as was I.

Ditto, Neil. Although I may rectify that, having read the resume of the younger brother’s story